In the museum and informal science education field we often place ourselves in opposition to amusement parks and theme parks. My own museum’s ED has said to our staff, “we have no pirates” in our museum.

From a certain perspective I think that makes sense. Amusement parks as private ventures have as their primary mandate to make money by offering experiences and goods that will part people from their hard earned cash. Museums and science centers, by contrast, have (hopefully) a commitment to public education, scientific research, civic engagement, and other ethical goals.

But having spent Thanksgiving weekend in Disneyland, I’ve thought a lot about what makes Disney work as a public entertainment experience. Here’s some fairly random thoughts that I’m working through.

Multi-generational Engagement

One of the marks of a successful theme park is its ability to appeal to many different kinds of audiences. Whether you are 5 or 85, there should be something for you that you will enjoy, which I think Disneyland accomplishes:

For the very young, there are specific rides and experiences designed just for them like Toontown, Disney characters walking around, and It’s a Small World.

For the very young, there are specific rides and experiences designed just for them like Toontown, Disney characters walking around, and It’s a Small World.- For the teenagers, there are thrill rides that they can enjoy, like Tower of Terror and Space Mountain.

- For adults, there are grown up restaurants and even a bar or two, like in the Carthay Circle.

- For older folks, there are shows like Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln and the gentle steam boat and train rides. Plus plenty of places to just sit, have a beverage, and take in the ambiance.

Museums and science centers have traditionally appealed most strongly to to families with young children, organized school groups, and (if they are lucky) visiting tourists. So finding ways to attract teenagers, young adults, elderly folks and others to visit is an important strategy to remain viable as an institution.

Staff Service and Enthusiasm

One of the aspects of the Disney parks that has always impressed me is the high level of enthusiasm and commitment to service of nearly all the staff I’ve dealt with. From the guy selling ice cream to the ushers in the theaters to the young woman sweeping the street — they all seem happy to see you, eager to answer any question or respond to a request, and knowledgable about the park.

There’s a certain amount of acting involved, of course, just like any service industry. But the Disney “cast members” do it better than almost anyone.

For science centers and museums, those are important objectives for all of your public-facing staff — enthusiasm, helpfulness and in-depth knowledge about the institution. All it takes is one rude or sour employee to ruin someone’s visit.

Creating Emotional Impact

A great theme park can elicit a range of emotions from visitors — amusement, surprise, amazement, even fear. Experiences that have powerful emotions tied to them are the most memorable, and the ones you will return for again and again.

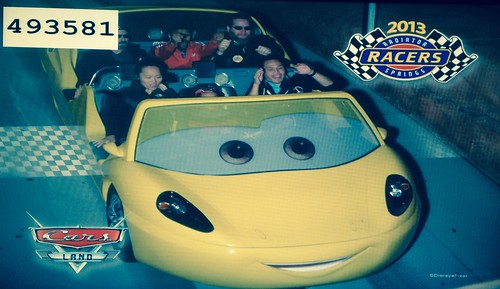

After riding the Radiator Springs Racers ride, I immediately wanted to get back in the line for another go. I remembered that feeling of delight at sitting in a pretend car driving down the Main Street from the movie “Cars,” the awe at the simulated canyons as we left the town, and the thrill of the race as we jockeyed for position against another car beside us. And in fact knowing what I experienced before enhanced the experience the next time, because I was expecting it.

As museums and science centers, we tend to focus on intellectual stimulation as a priority over emotional impact. But human beings thrive on and seek out experiences for a variety of reasons. So the challenge is creating experiences that elicit powerful emotions, while also informing and educating the public.

Social Experiences

People complain about the crowds at Disneyland. But really it would be no fun if it were empty. So much of the experience of what makes the Disney experience so engaging is the fact that it is being enjoyed by tens of thousands of people at the same time. (Daily attendance at Disneyland varies from 20-80K, according to statistics I’ve seen.)

Standing in line is part of the fun, believe it or not. Waiting for an experience creates a mixture of anxiety, excitement, and anticipation. Seeing all those hundreds and hundreds of other people queuing up with you for a ride affirms that there must be something really special at the end. And when you are finally on the ride, the satisfaction of the experience is that much greater.

I’ve actually been disappointed when the line for a ride like Star Tours is too short, because I don’t get to experience the fun of queuing up. Tower of Terror only works because of the entry way and build-up to the actual ride. Otherwise it’s just another ride that drops you really, really fast. I could say the same about several other rides at Disneyland.

Disneyland is a social experience. The park does a great job at making sure that people there as a family or a group get to stay together, if at all humanly possible. Because no one wants to be that one guy who had to ride by himself while the rest of his group were in a car together. The Disneyland imagineers understand that enjoyment of an experience is enhanced when its shared with others, particular friends and family that can amplify and relive the experience with us afterwards.

Museums and science centers can learn from this when they design exhibits and shows. Too many museum exhibits seem designed to be a single-person experience, rather than something shared. What is the experience like for people standing in line at your museum? What is the experience of families and groups of friends going together? What stories will they tell later about what happened?

A Mixed Reality Experience

Disneyland works as an experience because it is a rich blend of the familiar and the fantastical. People want to experience something novel, but they don’t want to leave behind everything that they know. Disney visitors like the fact that you can “travel” to a distant land or enter into a storybook adventure, while also enjoying a corndog and knowing where the nearest bathroom is. In fact its that juxtaposition of the familiar and the fantastic that makes it so compelling.

Bug’s Land in California Adventure is a great example. It’s in some ways just another amusement area with rides, restaurants and shops. But everything around you is designed to simulate being the size of an insect, from the benches fashioned to look like they were made of popsicle sticks to buildings decorated to look like they are giant cereal and candy boxes. It’s delightful running into tiny details in the architecture that remind you that you have been shrunk down to the size of an ant.

Museums and science centers can also think about how their spaces can mix the familiar and the surprising. How can we transport people to microscopic landscapes, outer space, deep in the rain forest, or under the sea? How can we elicit that “woah!” experience when visitors walk into our spaces?

Cautionary Notes

While I think there is a lot to be learned from theme parks like Disneyland, there are also aspects of Disney that should be avoided by museums and science centers. For example:

- Cost: Disney parks are INCREDIBLY expensive for your average family. Entrance starts at about $100 per person. Once you are in the park, everything is incredible inflated from a $4 bottle of water to an $18 plastic mouse-ear hat. That’s well beyond what a public institution should be charging to visitors, if we want to be accessible and open. (OTOH, I do believe the principle that people value more the things that they have to pay for.)

- Corporate Sponsorship: From the beginning, Disney parks have had rides, restaurants and more sponsored by difference corporations and even governments. That’s part of their revenue model. Museums and science centers often do the same, but have to be more careful about corporate ties that might diminish their credibility as science education and research facilities. General Motors probably shouldn’t be the only sponsor of your exhibit about transportation technologies, for example.

- Fake Science: There was LOTS of fake science in Disneyland that didn’t took me out of the experience. Showing people fake dinosaurs, fake coral reefs, and fake Africa is fine (I guess), as long as you aren’t representing them as reality.

- Draconian Employee Policies: Disneyland is notorious for their extremely strict employee standards and rules, particularly governing appearance, including hair length and style, tattoos, piercings, and eyeglasses. By many accounts, the hours are long, the pay is little, and the penalties for even the tiniest infractions can be severe. Museums and science centers should be inclusive places for our employees that welcome diverse styles and individual expression, and foster the well-being of our workers, as well as our visitors.

So to conclude, I’m not saying that everything that is done in Walt’s house should be copied by museums and science centers. But there are lessons to be learned and inspiration that can be gained from even the most commercial theme park experiences.

What else could museums and science centers learn from theme parks that can enhance our missions? I’d love to hear your comments and suggestions.